- Present

sandengine

Demo notes:

- Mobile input only available for basic actions such as placing pixels

- Performance on especially larger worlds is worse on web builds due to less performance optimizations and no multithreading support

There are native builds created by the CI for each release on the releases page that have better performance than the web demo.

Overview

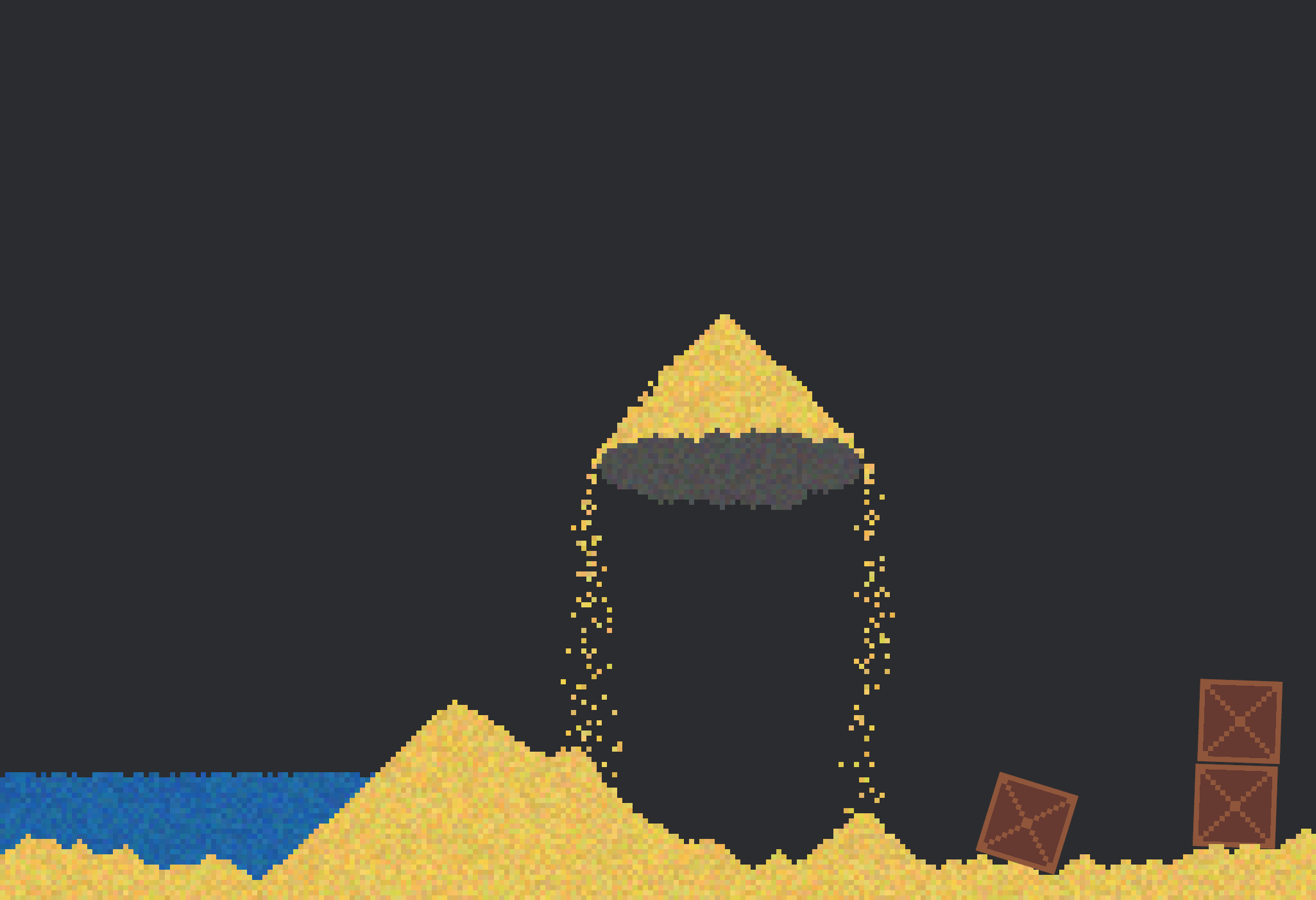

Sandengine is a falling sand simulation/game created in the Rust and using the Bevy game engine. The project aims to integrate traditional rigid body physics with the cellular automaton model of falling sand. This will allow for complex interactions between particles, such as bouncing off each other or being pushed around by external forces like gravity.

Current State

The engine is currently split into three modules:

-

Falling Sand Simulation: Handles the simulation of individual cell behaviors and interactions. This system uses a cellular automaton model to simulate sand, water, and other materials falling under gravity.

-

Physics Engine: Integration with the rapier physics library for rigid body dynamics. The physics engine runs on its own and for now handles spawning in objects from outside the simulation such as boxes or a player controller.

-

Particle Simulation: A basic particle system which is used for cells that are displaced by physics objects in order to search for empty locations.

There is 2-way interaction between these modules:

- Colliders in the physics engine are created for the falling sand simulation’s terrain, which allows the rigid bodies to collide and bounce off of the terrain.

- The rigid-bodies keep track of what cells they occupy and inform the cellular automata simulation each frame to prevent cells from falling into the body.

- Rigid-bodies with significant enough force can displace cells, turinging them into particles and allowing the rigid-body to move through cells.

Performance

A big part of the challenge with this project is with the goal to make it performant. With more features and a larger world size, the simulation will become increasingly complex and performance will degrade quickly.

To mitigate this, I’ve implemented several optimizations:

Falling Sand Simulation Optimizations

The falling sand “world” is managed separately from the Bevy engine’s gameplay loop in order to more efficently manage the data structures used for simulation. The world is split into multiple chunks in order to update the simulation only on a per-chunk basis, reducing the number of particles that need to be processed at once and allowing for parallelization.

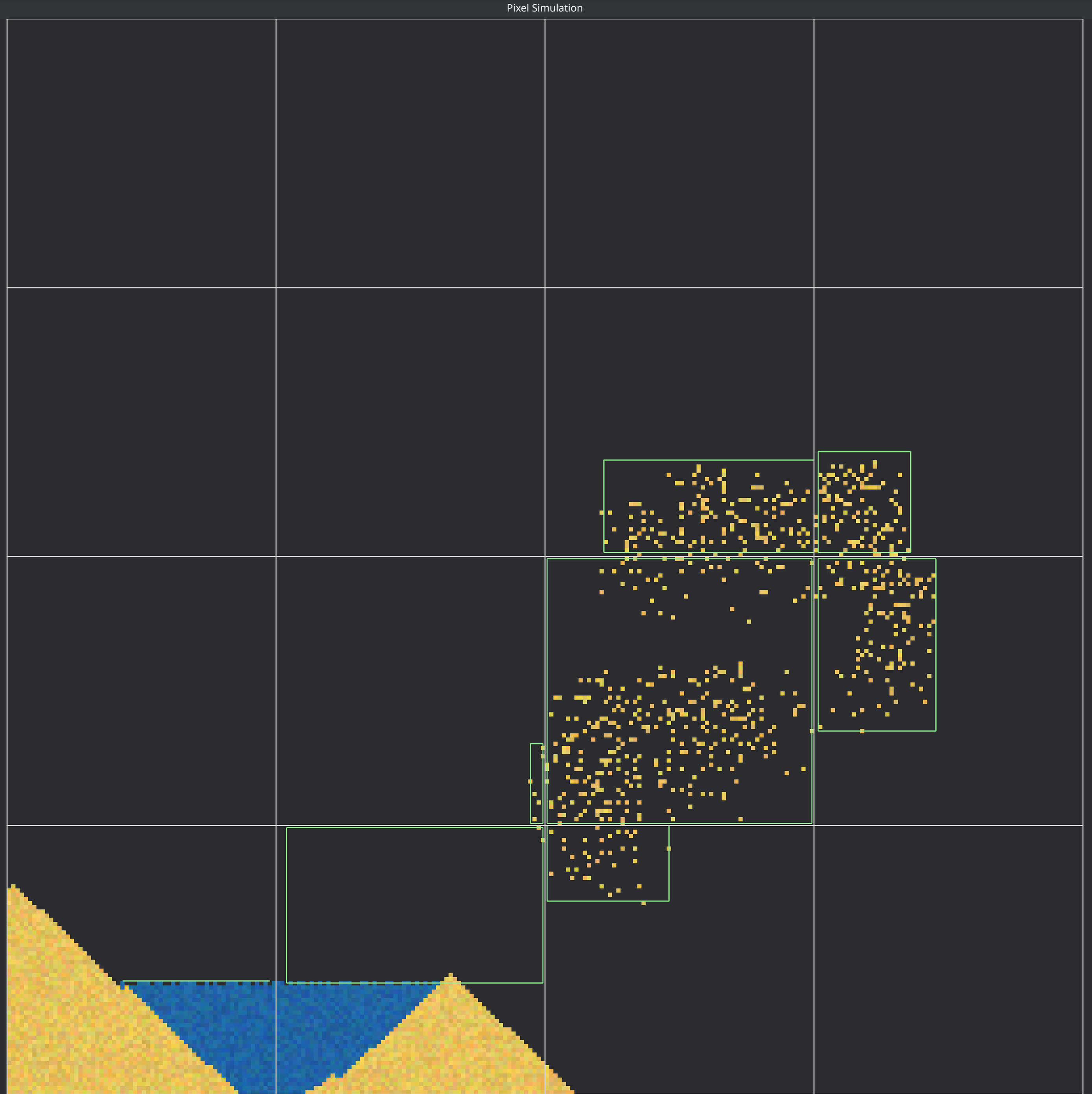

Dirty Rectangles

Another trick to achieve more performance (and this has given the most performance of any single optimization) is to utilize “dirty rectanlges” where only the part of the chunk that changed last frame should be checked for updates, rather than checking every particle in the entire chunk each frame. This reduces the number of particles that need to be processed by a large amount and allows for more efficient processing even without multithreading. For example in my (crude) performance profiling this opimization alone reduced the time spent updating sand from 330us to 35us (~9.4 times improvement) when there is no sand being updated anywhere, as the simulation can check then skip every chunk.

- Rendering is also chunked, with each chunk having it’s own image that the cell data is pushed to. These are also not updated if there were no changes to the simulation data within the chunk.

Image of the program running with the chunk debug rendering mode enabled: The grey outline indicate chunk boundaries while the green boundaries are the processing dirty rectangles for each chunk

Multithreading

Using task pools provided by the game engine, we can concurrently process large amounts of chunks at a time. On larger worlds this speeds up the cell processing significantly if many chunks need updating. A task pool is also used when generating the colliders for each chunk’s terrain if needed which can help if multiple chunks need colliders regenerated. Multithreading is accomplished by updating the world in a “checkerboard” pattern with four iterations per update frame. This keeps adjacent chunks from updating in the same iteration on different frames.

- This technique is explained in the Noita GDC Talk

- In Rust, we need to use unsafe in order to split the chunk’s worlds across multiple threads so that they can move cells between chunks.

- This is accomplished using the UnsafeCell container.

- Although unsafe is used, we know that cells will not be accessed at the same time because the cellular automata cannot move fully across a chunk in one iteration.